In the words of its authors Brad Meltzer and John Mensch, “The Lincoln Conspiracy” is “the story of an early conspiracy to kill Abraham Lincoln – before he served a single day as president, and on the eve of the terrible war that would define his place in history.” Get ready to learn all about it!

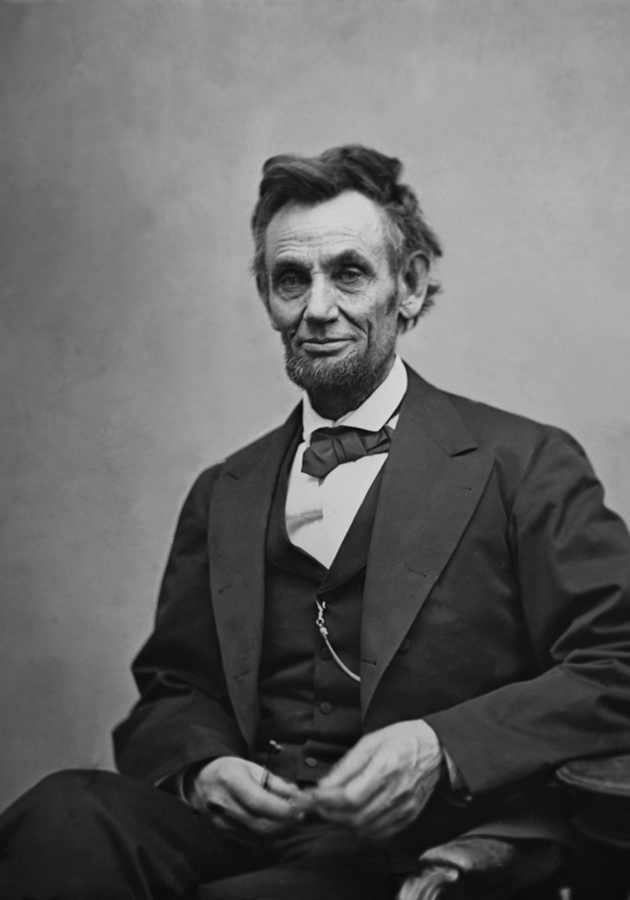

Abraham Lincoln, President of the North

On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States. Though decisive, his victory was entirely due to his support in the North and West. In fact, he was so unpopular throughout most of the South that the Republican Party didn’t even distribute ballots for him. As a result, not a single person voted for Lincoln in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, North Carolina, Florida, Tennessee, or Texas. For Southerners, Lincoln was a President of the North. He was not their President.

Shortly after the election, this sentiment was made clear by many newspapers in the South. “A party founded on the single sentiment of hatred of African slavery is now the controlling power,” announced the Richmond Enquirer. A New Orleans editor concurred: “The Northern people, in electing Mr. Lincoln, have perpetuated a deliberate, cold-blooded insult and outrage upon the people of the slaveholding states.” An Arkansan writer was even more worried and less subtle, saying “The Republicans are organized into military companies, and intend to march against the South […] to cut the throat of every white man, [and] distribute the white females among the negroes.”

Barely six hours after Lincoln’s victory, the members of the South Carolina General Assembly convened and passed “a hastily crafted resolution” entitled the “Resolution to Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President a Hostile Act.” They didn’t want to risk anything: after all, more than 57% of the population of South Carolina were enslaved people at the time. Five weeks later – at approximately 1:15 p.m. on Thursday, December 20, 1860 – South Carolina became the first state since the founding of the country to formally secede from the United States of America. By February 1 of the following year, six other states had joined in: Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. From county to county, voices were raised vowing that the president-elect would never reach the Capitol to be inaugurated. Still not sworn in, Lincoln became persona non grata in his own divided country.

Lincoln and his lifelong friend: Death

Election night was an exhausting affair for Lincoln. After the initial enthusiasm of the victory had passed, he started feeling the oppression of “the load of responsibility” laid upon him. Some three hours after midnight – unable to fall asleep – he glanced at a mirror affixed to a bureau across his room. “Looking in that glass,” he would later describe the strange premonition, “I saw myself reflected nearly at full length; but my face, I noticed, had two separate and distinct images, the tip of the nose of one being about three inches from the tip of the other.”

Though prideful in his scientific mind, Lincoln wasn’t able to discard the vision as the product of fatigue or a trick of the light. The double image of his face – and the ghostliness of one of the faces – seemed to him as some sort of an otherworldly omen, suggestive of death. “The mystery had its meaning, which was clear enough to him,” Ward Hill Lamon – a friend and self-appointed bodyguard of Lincoln – would recall decades later. “To his mind, the illusion was a sign – the life-like image betokening a safe passage through his first term as President; the ghostly one, that death would overtake him before the close of the second.”

In retrospect, there were thousands of clues that justified this kind of interpretation – or, more specifically, thousands of personally addressed letters. As Lincoln’s trusted secretary and aide John Nicolay noted at the time, just a day after the election, “his mail was infested with brutal and vulgar menace, and warnings of all sorts came to him from zealous and nervous friends.” Another Lincoln colleague described the situation in even more vivid language: “There were threats of hanging him, burning him, decapitating him, flogging him.” Unsurprisingly, Lincoln’s friends feared very much for his safety.

Lincoln, however, was seemingly unruffled. On the contrary: even as the Southern states began seceding from the Union, Lincoln began preparing to relocate from his home in Springfield, Illinois to the White House. On his way to taking the oath of office, he planned a grand 2000-mile 13-day whistle-stop tour through more than 70 cities and towns. But his enemies were planning something far more sinister – to kill him along the way. Intuitively fearing such an outcome, a friend by the name of Hannah Armstrong warned Lincoln to be careful. “If they kill me,” replied half-jokingly Lincoln, “I shall never die another death.”

A reformer, a railway executive and a real-life Sherlock Holmes

On February 11, 1861, the “Lincoln Special” – the president-elect’s private train – began its journey from Springfield, Illinois, to the city of Washington. The tour required a lot of planning, as it included numerous timed stops and train changes, as well as meetings with local politicians and overnight stays at hotels – not to mention a two-day trip deep into enemy territory. Samuel Morse Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, was particularly interested in the last part. But not chiefly for business reasons.

You see, one month before the Lincoln Special’s scheduled departure, a well-known reformer and educator by the name of Dorothea Dix had arrived in Felton’s office and shared with him some “alarming plans” whose objective was “to prevent, at any cost, the inauguration of the new president.” As Felton would later recall, Dix told him, “there was a deep-laid conspiracy to capture Washington, destroy all the avenues leading to it from the north, east, and west, and thus prevent the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln in the capital of the country.” And, “if this plot didn’t succeed, then to murder him while on his way to the capital, and thus inaugurate a revolution.”

Felton immediately approached Baltimore Police Marshal George P. Kane with this information, but Kane – a proslavery Democrat and a Southern extremist – casually dismissed the threat. Frustrated with the lack of action, Felton turned to “a man of great skill and resources,” the only one who could help him with this matter of national importance: Allan Pinkerton, a Scottish cooper. Of course, he was much more than that: a detective, a spy, and the world’s first “private eye.”

Spies in disguise, I reckon

Felton’s letter to Pinkerton arrived on January 19, 1861, and immediately aroused him to “the realization of the danger that threatened the country.” He accepted the case and, after a meeting with Felton, set off for Baltimore, Maryland – the suspected focus of the plot. Assuming the identity of Alabama stockbroker John H. Hutcheson, he tried to infiltrate secessionist circles by renting an office at 44 South Street, just near Baltimore’s busy commercial district. He was not the only spy in the city. His fellow detectives, Harry Davies and Kate Warne, were making the rounds as well – the former posing as a New Orleans aristocrat, and the latter as a flirting “Southern belle.”

Davies’ role was to gain access to the privileged social world of Baltimore’s young elites. In just a few days, he won the favor of Otis K. Hillard, a 28-year-old member of a privileged Baltimore family. With the help of some alcohol, Davies swayed Hillard into revealing the existence of a powerful Southern organization interested in the head of Lincoln. Meanwhile, hovering around places such as the classy Barnum’s Hotel at Calvert and Fayette Streets, the graceful and ever-reliable Warne used her well-polished and thick southern accent to seduce young Southern secessionists into telling her many key details of how the supposed assassination of Lincoln was going to occur.

The final proof came just days before Lincoln’s scheduled arrival in Baltimore. On February 14, Pinkerton heard a stockbroker named Thomas Luckett – an avowed secessionist working in an office on the same floor as him – cursing Lincoln and mentioning an armed anti-Republican organization. Still disguised as Hutcheson, Pinkerton ceremoniously handed $25 (roughly $750 in today’s money) to Luckett. “I should be obliged,” the detective said, “if [you] would see that this was employed in the best manner possible for Southern rights.” Impressed, Luckett offered to introduce Pinkerton to the head of the organization. He calmly agreed.

The barber, the Knights and a most fiendish plot

At 7:00 p.m. on February 15, 1861, Pinkerton, posing as stockbroker John Hutcheson, entered the Barr’s Saloon on South Street. There, he saw Luckett seated with “several other gentlemen,” one of whom introduced himself as Captain Cypriano Ferrandini, a Corsican immigrant.

A fine-looking 30-year-old with a trimmed moustache and a charming voice, Ferrandini was known to many citizens of Baltimore as the longtime barber and hairdresser in the basement of the Barnum hotel. To the few people at the table, he was much better known as a renowned member of the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC), a white supremacist organization whose goal was to annex large territories of the South, Mexico and the Caribbean and establish a slave empire.

It didn’t take long for Pinkerton to discover that Ferrandini was also the architect of the conspiracy to kill the president-elect. “Never, never shall Lincoln be President!” the barber cried out at one point during the night. “Murder of any kind is justifiable and right to save the rights of the Southern people. If I alone must do it, I shall – Lincoln shall die in this city.”

The plan, Pinkerton surmised, was chillingly simple. Since the itinerary for Lincoln’s train trip was known in advance, Ferrandini and the Baltimore branch of the KGC knew the exact moment the president-elect was supposed to change trains in their city. So, they intended to assassinate him then, in the early hours of February 23, 1861, during Lincoln’s one-mile transition between the Calvert Street and Camden Street stations.

Pinkerton wasn’t sure about the method. It was either going to include a diversion to draw the attention of the police and allow one man to kill the president-elect or several assassins dispersed in the crowd. Either way, there was a plot and a plan to assassinate the incoming president. As the only outsider aware of it, Pinkerton realized that he might be the only person alive who could stop it.

“I would rather be assassinated…”

On February 21, Pinkerton traveled to Philadelphia to divulge the facts of his investigation to Felton and, by special request, Norman Judd, a friend and confidant of Lincoln. Judd immediately arranged a meeting between Pinkerton and Lincoln in his hotel room and, just 36 hours before the assassination was to take place, these two exceptional men met for the first time.

The detective revealed the assassination plot to the president-elect and suggested he did the only sane thing: immediately change his schedule. To his surprise, Lincoln declined. He wasn’t going to change anything before raising a flag over Independence Hall in memory of his hero, George Washington, and visiting Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. “Any plan that may be adopted that will enable me to fulfill those two promises, I will carry out,” Lincoln said before leaving the room.

Six hours later, he stood before the redbrick walls of Independence Hall and, under a waving American flag, delivered an impromptu speech on the hallowed sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence and its overarching principle of liberty. “If this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle…” he uttered at one moment, trailing off. “Well, I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender it.” The audience cheered. Little did they know that just a few hours earlier, Lincoln had learned that there was a very real plot to assassinate him, and that his life was most certainly in danger.

A daring escape that decided the fate of a nation

Around 5:45 p.m. later that day – as he was dining at the Jones House in Harrisburg in the company of Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin – Lincoln felt a tap on his shoulder. It was a signal. He slipped out a side door of the hall and, feigning a hump to mask his height, limped into a waiting carriage, where he threw on an atypical overcoat, a wool shawl, and a soft, wide-brimmed hat. As soon as he departed Harrisburg, the telegraph wires were cut to ensure that nobody in Baltimore would find out.

At 6:00 p.m., in the company of Pinkerton and his bodyguard Lamon, Lincoln boarded a Pennsylvania Railroad train for Philadelphia and five hours later switched to an 11:00 p.m. Baltimore-bound train. There, the three men were greeted by Pinkerton’s agent Warne who, posing as the sister of an invalid traveler had already reserved four berths for the party in the back of the sleeping car. The invalid traveler was, of course, none other than Lincoln.

At 3:30 a.m. on February 23, this curious party of four arrived at Baltimore’s President Street depot. This was the critical point. Since rail travel wasn’t allowed through the city at night, Lincoln’s car had to be unhitched and drawn by horses to Camden Street Station. There, it was to be attached to the connecting train to Washington D.C. Fortunately, even though the car passed within about four blocks of Barnum’s City Hotel, no conspirator noticed anything. A few hours later, as Ferrandini and the other Knights started preparing to enact their violent plan, Lincoln was already in Washington, where he could finally get some rest after 48 hours of wakefulness and worry.

It was to be a short-lived rest. When he woke up, journalists had already found out about the whole affair, and everybody was talking about Lincoln sneaking into the capital as a thief in the night. Most newspapers branded him a coward and questioned his manliness. Over the following four years, Lincoln would prove all of them wrong, successfully escorting the United States through its greatest crisis as the greatest of leaders. He is today known as the man who preserved the Union and abolished slavery in the midst of a bloody war. However, nobody knows if either of these things would have happened if a railroad executive hadn’t hired a private detective to investigate a rumor heard by a social reformer in the first month of 1861!

Final Notes

The Knights of the Golden Circle continued to operate throughout the Civil War, but fell into a disarray sometime late in 1863. At its peak, listed among its members was a stage actor by the name of John Wilkes Booth. On April 14, 1865, at the Ford’s Theater in Washington, he did what Ferrandini and his conspirators couldn’t do four years earlier in Baltimore: he assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

Fortunately, by then, it was too late to reverse any of Lincoln’s revolutionary policies. Lincoln died, but his ideas and ideals carried on. They are still the foundation of America’s greatness. A gripping narrative, “The Lincoln Conspiracy” reveals how close the country might have been to never even laying the proper groundwork.

12min Tip

The United States – write Meltzer and Mensch – is not just a country of ideas, but a country of ideals. “What makes America exceptional,” they write, “aren’t our weapons or our might. It’s our principles and our continuing fight to live up to them. Faced with darkness, we must reach for the light.” Lincoln did that. Try doing it yourself.